⚖️ How to Measure a Tabletop Roleplaying Game

This is part one of a ?-part series I've taken to calling New PEGS, or "New Principles of Epic Gameified Storytelling" ...though to be honest, "New Principles of Storytelling Games" rolls off the tongue better, even if it doesn't quite work with the acronym. :)

I started playing Dungeons & Dragons when I was 13 at an independent game store in Redmond, Washington—with a group of smart, funny, and in hindsight unusually patient twenty-somethings. Since then, I have spent countless hours playing table-top roleplaying games, developing stories and campaign settings, and even writing my own games.

D&D and all the progeny of its genericide have been an enduring passion of mine for over half my life. Over time, I've come to want better language for talking about the distinct characteristics of storytelling game systems—beyond what is "good" or "bad." People come to these games looking for a variety of flavors, and different qualities appeal to different people. My efforts coalesced into four distinct axes: in no particular order, these are jeopardy, regulation, continuity, and symmetry.

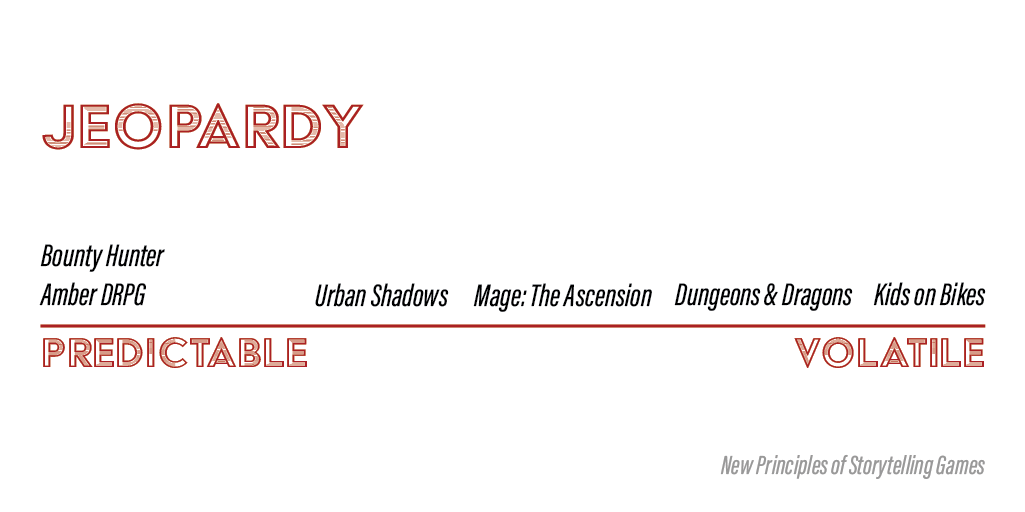

Jeopardy is the measure of any game outcome’s dependability. On the far left are entirely deterministic games like Bounty Hunter or Amber DRPG, in the middle are games that require rolling more than one die like Urban Shadows—or allow players to improve the odds of important rolls, like using Willpower or Quint in Mage: The Ascension. And on the far right are games where a single, polyhedral die-roll decides the fate of any check, as is true of Kids on Bikes.

In practice this represents how much chaos you are willing—or even excited—to accept at your table. There is a thrill to knowing that however great a pick-pocket or poor a swordsman you may be, there is a 1 out of 20 chance that the die decides your fate.

Personally, I've come to appreciate the added level of confidence in systems with normal distribution; illustrated for example by the success curve on two six-sided dice common to most Powered by the Apocalypse games. Knowing that you're more likely than not to succeed encourages players to act and take risks—and makes the failures feel even more dramatic.

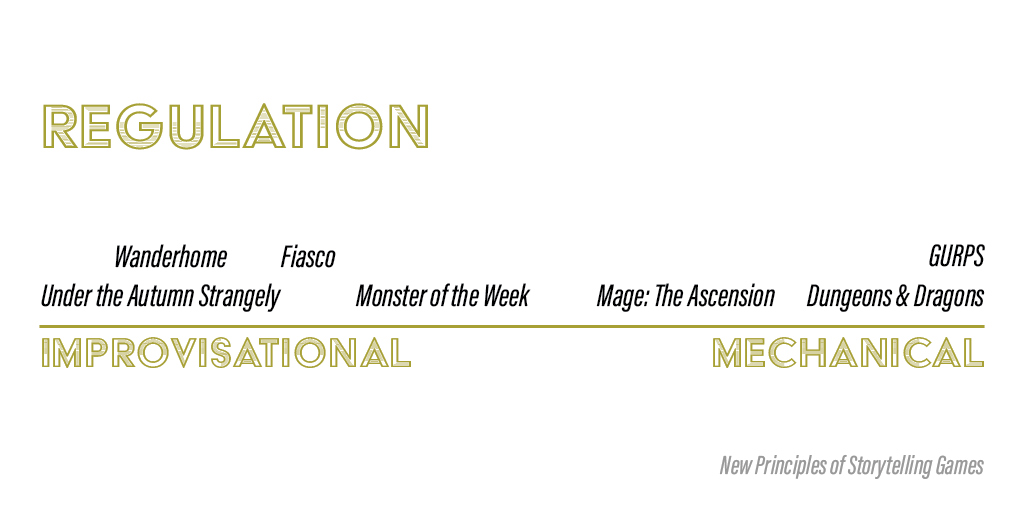

Regulation is the measure of a game’s reliance on rules for the resolution of action, versus storytelling, roleplay, and extemporaneous decisions made by the GM or player. In almost all games with a GM, they are given a broad mandate to improvise as necessary. But some games lean into this, with a lighter-weight structure. Another way of thinking about regulation is as what percentage of all possible activities/outcomes are covered unambiguously by the rules. On the left are highly improvisational games like Wanderhome, in the middle storytelling-focused games like Mage and Vampire: The Masquerade. On the right, “crunchy” games like Dungeons & Dragons or GURPS.

At the table, both ends of the spectrum can be overwhelming to newcomers. Loose structured games ask players to bring a lot of themselves to every session, with little in the way of abstraction between character, story, and play. In this sense, improvisational games are a straightforward evolution from the imagination games we played as children. Regulated games, on the other hand, ask players to learn a lot upfront—cousin to the infamous board game night in all its booklet-flipping glory.

At risk of showing my current bias once again, I do think a big part of PbtA's great success is that is best positioned on this axis for broad appeal. There are enough mechanics to provide structure to shy or reserved players, and enough room for imaginative play for those who want to learn on the fly to have a good time doing it.

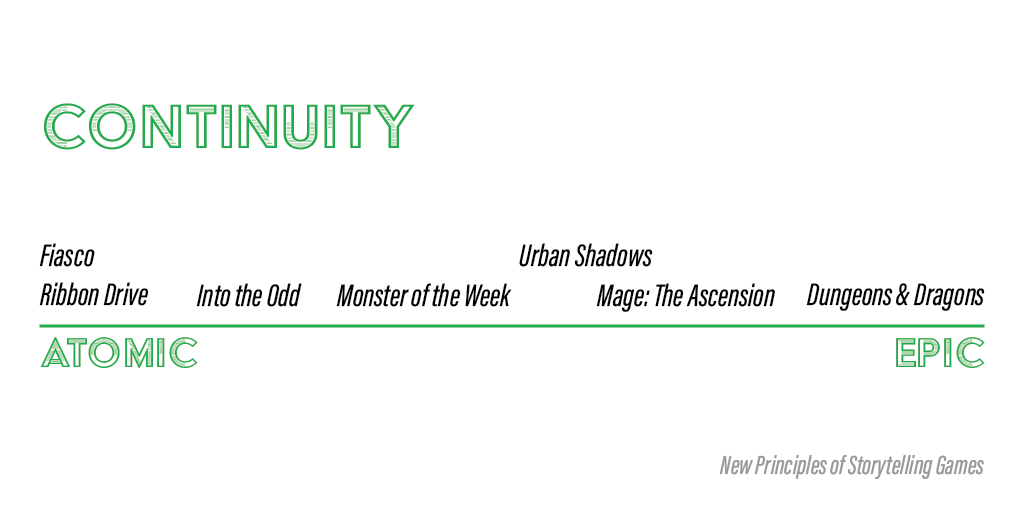

Continuity is the measure of a game’s emphasis on long-term storytelling vs short, as well as to what extent the game is designed to favor long arcs with specific characters. On the left are one-shot and OSR games like Ribbon Drive or Into the Odd. In the middle are games that encourage episodic play or have built-in character retirement like Urban Shadows. On the right are games optimized for playing long-running campaigns with nearly unbounded advancement, like Mage: The Ascension or Dungeons & Dragons.

The greatest threat to the lifespan of a campaign is not a red dragon or the ancient blade of a titan falling from orbit—but the dreaded fizzle following a series of scheduling snafus. Great games that require fewer calendar resources can be perfect for groups of adults who don't want to commit to Tomb of Annihilation (does anyone else hear Guns N' Roses start playing whenever they think of that adventure?) While it's possible to run a one-shot of D&D, Fiasco is designed to combine the imaginative fun of roleplay with the self-contained simplicity of a party game.

I've historically gravitated towards years-long campaigns, forever chasing the high of my first 2nd - 32nd level game of 3.5... and this is one axis on which my preferences have not shifted much. But in recent years I've come to really appreciate an emotional roadtrip game (seriously, play Ribbon Drive) with a complete story and a satisfying emotional arc realized in one night.

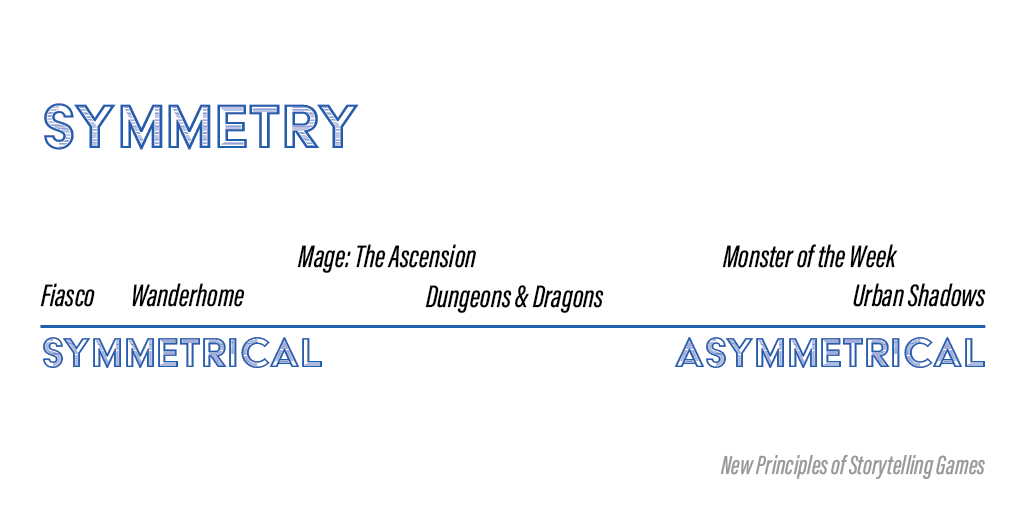

Symmetry is the measure of a game’s likeness of each participant’s experience, including that of the game master, if there is one. On the far left you will find GM-less games like Fiasco and Wanderhome. In the middle, classic TTRPGs like Dungeons & Dragons with a Dungeon Master or Storyteller, and on the right, games involving more unique play styles for different character classes or a separate set of rules for the game master and their NPCs, common in PBtA games like Monster of the Week and Urban Shadows.

While the Dungeon Master / player binary may seem inherently asymmetrical, the most popular tabletops published by White Wolf, TSR, and Wizards of the Coast in the 90s and 2000s expected the GM to abide by the same rules as the players, at least once the dice started rolling. All D&D classes share the same set of skills to choose from, and combat can feel very much like a strategy minigame—albeit one where the DM can deploy new troops or complications at their discretion.

When I first played Monster of the Week, the truly asymmetrical nature of the player / game master relationship felt strange and uncomfortable. In many PBtA games, the GM—or "Keeper" in the case of MotW—is given license to use a unique set of "soft" and "hard" moves. Soft moves can be evaded or mitigated by the players—hard moves cannot. This felt counterintuitive, and still sometimes does when I'm running my home game of Urban Shadows (we take turns MC'ing, my friend Darren is much better at it than me). But I do think there's something more honest, or perhaps just more accurate, about explicitly framing the relationship in mechanically different terms.

What's next?

So what's the point of this exercise? Well, like I said at the beginning, it's helpful to have specialized language to discuss the qualities of the things we love. But having that framework can also help you understand what you love, and focus on what you want to bring out in your games.

I think it's also interesting to consider the placements of popular games, and whether these qualities are inherently correlated. Must an asymmetrical, semi-regulated game always have episodic continuity as well? Or could a game be designed with the beginner-friendly rules of Monster of the Week that's just as good for epic tales of gods and monsters as D&D?

Any vacuum is an opportunity to innovate; and however amazing these games are today (I mean seriously, how lucky are we?) the games of tomorrow could be even better.